The importance of street trees in North Philadelphia grows as climate change worsens

The lack of street trees in North Philadelphia is alarming, but change is happening

PHILADELPHIA, Pa. — As spring grows whole in the city where cherry blossoms are aplenty and glimpses of hot sunny days peek through clouds of late April, North Philadelphians are reminded that summer temperatures on their simmering streets will be unbearable for yet another year.

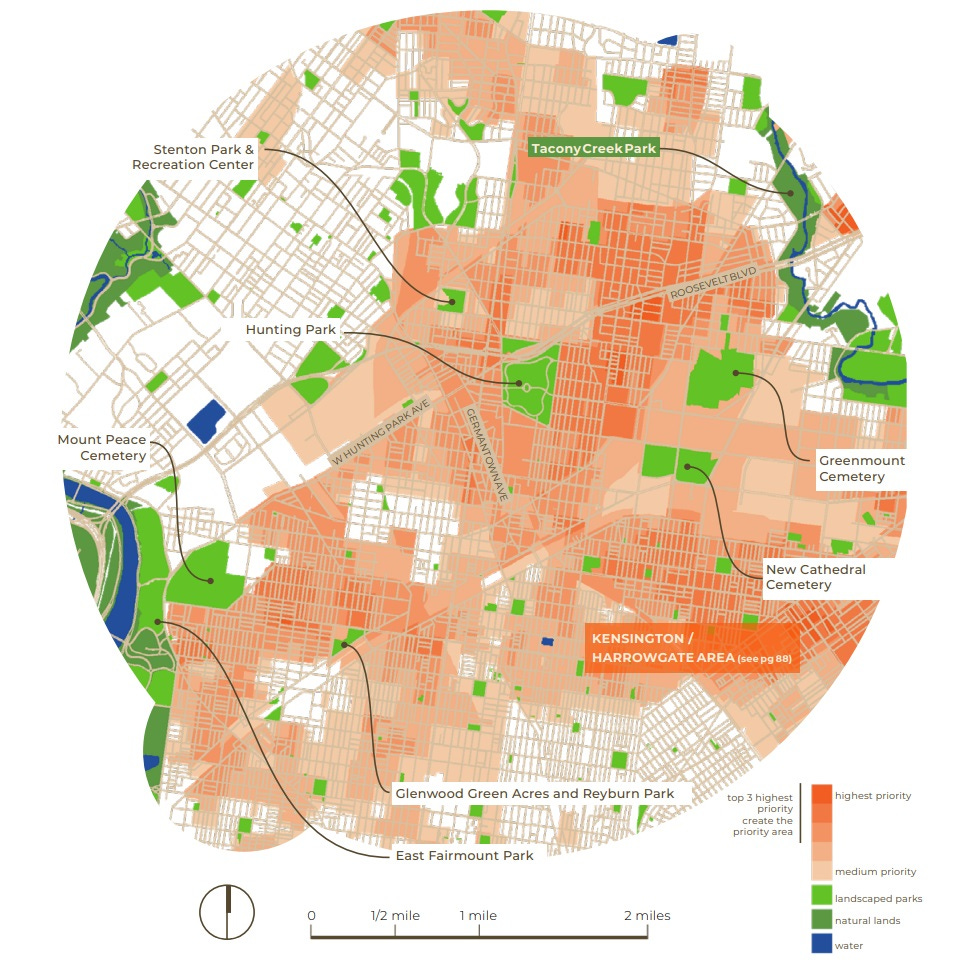

Treeless streets are all too common in North Philadelphia’s neighborhoods. Blocks upon countless blocks are barren—the only greenery for wide concrete stretches comes from vacant lots left to flourish in thick vines and weeds, and the only shade to be had is the product of looming row houses. In Hunting Park, a predominantly Black neighborhood in the heart of North Philadelphia, residents suffer from temperatures that can soar up to 20 degrees hotter than the city average on any given day. This unfortunate phenomenon is known as heat island effect and can have grave consequences for residents unprepared for sweltering summer heat.

But less than two miles south, Philadelphia’s affluent Center City residential areas are flush with old blooming oak and ash trees towering over brick lain sidewalks and the red brick brownstones they sit beneath. Shade is bountiful in neighborhoods like Rittenhouse, Washington Square West, and Fairmount, as they host a glorious abundance of trees on their sidewalks.

The glaring disparity in tree canopy coverage between neighborhoods in North Philadelphia as compared to neighborhoods in Center City is clear. The other main difference between the two areas is that North Philadelphia’s neighborhoods are predominantly Black and have been historically working class, while Center City’s affluent neighborhoods are made up of a majority white demographic and have not dealt with the same generational issues as communities farther north.

“Over the last five years, there’s been a lot of research connecting the long legacies of discriminatory housing policies like redlining to the present day issue of having low tree canopy coverage,” says Hamil Pearsall, a Geography and Urban Studies professor at Temple University who has done extensive research on street trees in Philadelphia. “So neighborhoods that were historically redlined suffer from long term environmental impacts like having low canopy cover and have hotter temperatures because of it.”

Jasmin Velez, a community organizer for Kensington Corridor Trust, agrees.

“Environmental racism is a thing. These issues are seriously tied into social inequities and racism as a whole,” she says. “You know, where is the money being invested? Things like white flight happened. I would argue that the lack of street trees are a blend of all these different social issues that happened and left some communities more disinvested in than others.”

Velez also mentions the overlap between urban heat island maps and historical redlining maps.

Heat island effect occurs in urban areas across the country. According to WHYY, over 440,000 Philadelphia residents live in areas that can get 9 degrees hotter, while over 1,000 people live in areas that swelter to at least 12 degrees hotter.

“Because a city has so much grey infrastructure like sidewalks, buildings, and things that are impervious, you essentially have a concrete jungle that has a pretty instinctual effect, which is that heat is held in all of those materials,” explains Cheyenne Flores, a program manager in the city’s Office of Sustainability with expertise in energy infrastructure.

“There’s something called the albedo effect, which makes dark colored surfaces an issue as well. They absorb heat and reradiate it, often at night, so it’s really kind of like a double whammy,” she continues. “So when the temperature has cooled, now everything is off gassing—essentially, the heat that it was storing in the day gets let out, which keeps everything hot. It’s essentially a heat dome that gets created. In other parts of the city you have greenery and maybe even water to take on all that heat from the sun, whereas some parts of the city just absorb, absorb, absorb.”

Many of Philadelphia’s flat top roofs are dark colored and what offsets those impervious surfaces are amenities like street trees and water. But the parts of the city that take on the most absorption due to immense amounts of impervious surface create pockets of vast differences in temperature, hence the name heat “island.”

Beyond heat island effect, having more trees in North Philadelphia would likely create a greatly improved environment for all who live there. Street trees are linked to lower crime rates, lesser litter and trash problems, as well as have the ability to prove mental health. North Philadelphia is in dire need of bettering all three of those things.

A study done by the US Forest Service in Baltimore concluded that a 10% increase in a neighborhood’s tree canopy was associated with a 12% reduction in crime. A University of Washington study in 2010 found that public housing buildings with high levels of vegetation (such as trees) saw a 52% decrease in total crimes, 48% decrease in property crimes, and 56% fewer violent crimes as compared to public housing buildings with little to no vegetation. And in Philadelphia, a 2017 study found that the number of gun assaults were reduced when there was a presence of tree cover.

Mental health can rapidly change because of nearby street trees as well. Greenery in general has links to drastically improving one’s well being. According to the World Economic Forum, a study decided that living within 330 feet of a single tree could be enough to lessen the need for antidepressants.

But there can be a downside to having trees on sidewalks. Income related issues and ADA-accessible compliances can make a street unviable to host trees.

“The way street trees work in Philadelphia is even though the city owns the sidewalks, property owners are responsible for maintaining the sidewalks and the trees in them,” says Pearsall. “Maintaining existing trees can be really challenging for residents and community members.”

Many people outside of aforementioned neighborhoods like Rittenhouse and Fairmount are unable to afford tree maintenance. Jasmin Velez believes that’s another reason why there are so few street trees in North Philadelphia.

“If a tree impacts your sewer line, it can cost up to $3,000 to fix,” she says. “So if we are looking at communities like North Philadelphia, those folks who are predominantly low income, maybe moderate income, don’t have three or five grand to spend on stuff like that. As much as they may want the tree, there’s this level of fear that comes into play.”

Pearsall agrees.

“Let's say there was a tree that was growing and residents felt like the city wasn't doing their part to maintain that tree. So again, even though the city technically should have been caring for the tree, homeowners ended up having to do the pruning or had to, you know, have the tree removed so it didn't become hazardous,” she hypothesized. “So people came to kind of distrust that the city would take care of the trees, so they removed them rather than having a limb come down and crush their car and then being liable for it. It was easier and more risk averse to not have trees.”

According to Velez, there aren’t any programs in place to help homeowners maintain the trees on their sidewalks.

It’s abundantly clear that Philadelphia has a street tree problem. It’s ranked last in tree canopy cover in all major northeastern cities. Huge disparities in canopy coverage exist between low income and high income neighborhoods. And from 2008 to 2018, the city lost over 1,000 acres of tree canopy.

But in 2023, the city released the Philly Tree Plan, a ten year strategic plan for how to increase and maintain Philadelphia’s existing tree canopy over the next ten years. For funding, the city budgets the US Forest Service dished out a $12 million grant to local nonprofits to make sure the tree plan is seen through, a vast improvement from the $2 million annual budget for Philly’s tree canopy.

One huge difference maker that has been sparking change city wide and helping to implement the Philly Tree Plan is Pennsylvania Horticultural Society’s Tree Tenders program. According to their website, the program’s entire goal is to plant trees through volunteer-based community work. The program holds workshops for learning how to plant and care for trees. On average, the Tree Tenders plant over 3,000 trees per year.

Street tree planting takes place in April and November. As the spring planting season wraps up, hundreds of more trees have been planted by PHS’s Tree Tenders program on Philadelphia’s needy sidewalks. But how can more Philadelphians get involved?

“Advocating to our lawmakers, writing letters to council, showing up to council meetings, and getting involved that way is the first piece into making it known that [street trees] are a priority in this city,” says Asha-Lé Davis, a tree expert who works for the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society. “As constituents, we have a lot of power.”

Davis believes that the new mayor, Cherelle Parker, is open to proposals for exponentially growing Philadelphia’s tree canopy.

But beyond politics, it’s an easily traversable course for Philadelphians to see more trees planted not only in North Philadelphia, but throughout the city as a whole. PHS has a program where homeowners can request a street tree to be planted outside of their home, free of charge. Specific directions can be located on their website.

But what if you’re not a homeowner? According to the US Census, only 52.2% of Philadelphians own their homes. That means over 360,000 homes in the city are rented out by landlords and getting landlords to reach out to PHS may be a serious difficulty.

“We have a template that is a homeowner letter and it explains all the benefits of street trees and really highlights that this can help increase property value,” says Asha-Le Davis. “There are a lot of renters that are passionate and want to plant trees but just need their homeowner to sign off on it.”

To get the homeowner letter template, Davis said to reach out to trees@pennhort.org.

Volunteering is another huge opportunity for individuals to create real change and grow Philadelphia’s tree canopy. This past Earth Day weekend, hundreds of trees were planted across the city by volunteers and members of PHS’s Tree Tenders program. A map of future tree planting events can be found on the PHS website as well.

“We are planting 1,100 trees throughout the region this spring. 550 or so are going into Philadelphia,” says Davis. “75 community groups work to get these trees planted. That's the beautiful thing about these tree plantings, we work with community groups, volunteers. There are people who are truly passionate about bringing this amazing resource to communities.”

Davis hopes to see an abundance of trees planted by even more volunteers in the coming months and years. Jasmin Velez is excited for the future too.

“The Philly Tree Plan and everything else is so exciting because, historically, we’ve had a city that hasn’t really been engaged around these topics so much, so there’s a lot of push to support these initiatives and the work that they’re doing because we’re finally thinking about these things a little bit deeper,” concludes Velez. “I’m not saying it’s going to change tomorrow, right? The policy and advocacy work takes years sometimes, but we are moving in the right direction.”